Influencer marketing didn’t exist a decade ago, but now it’s the height of fashion when it comes to social media marketing and brand awareness tactics. Communicating with potential consumers and a new, targeted audience by working with influencers is expected to give an air of believability and authenticity to brand campaigns. But is that expectation starting to fall out of touch with reality?

Marketers love content marketing because it avoids the advertorial – a healthy amount of time and money is spent on making sure that marketing doesn’t make people feel like they’re being sold to, with stats consistently showing that around 75% of marketers look to increase their content spend each year. One recent survey, reported in Mediakix, found that 84% of companies surveyed were planning to work with a social media star as part of their next content campaign, a substantially higher figure than the 65% who said they would be using traditional blogging.

But another survey, recently undertaken by Prizeology, found that 44% of respondents disliked influencer marketing so much, they described it as ‘damaging to society’. So what are marketers to do?

The digitalisation of C2C Marketing

Bring influencers into the mix, and we go from B2C to C2C marketing – with the illusion being that social influencers just happen to love brands and products so much that they use and mention them all of their own accord. While guest blogs have long been a popular way to get brand content placed in front of relevant eyes, influencer content engages because the audience genuinely care about the influencer and what they, personally, have to say. What are they wearing, eating, buying? Where are they travelling to, and how do they get there?

In practise, C2C marketing has always been the big winner for brands – but never before have brands been able to pass themselves off as fellow consumers. People have a natural tendency to tell their friends and families about products they love, and good experiences they’ve had, with 83% of consumers trusting peer reviews over advertising.

Travel, retail and hospitality brands have long known the power of user reviews, both online and offline, and data has shown that around 85-90% of online shoppers don’t just trust reviews more, but also incorporate these reviews into their purchasing decisions. Add social media into the mix, and suddenly consumer-to-consumer discussion becomes an engineerable, fakeable selling tactic.

The number of social media users grew by 121 million between Q2 and Q3 2017 – equating to a new user every 15 seconds. Facebook alone now has more than 2 billion users worldwide, with Instagram’s audience totalling a cool 800 million. That’s a lot of people watching what other users are doing, browsing profiles on the move and adjusting their spending habits in accordance with perceived trends and recommendations.

The rise of the micro-influencer

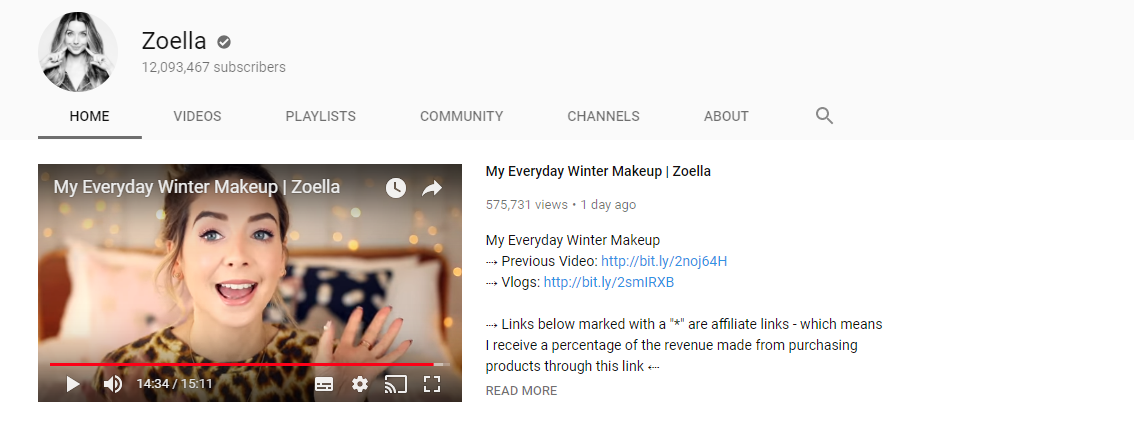

The time it has taken for businesses to figure out the best ways to use influencer marketing has been just enough for the first wave to crash. Big-name influencers with hundreds of thousands, even millions of online followers are falling out of fashion, as consumers wise up to the fact that people like Zoella and PewDiePie are being paid handsome sums to endorse particular brands.

Yes, they can get your product, your name, your offer in front of a huge audience of people – but there’s no longer a guarantee the audience will find the endorsement any more trustworthy than a sidebar ad. In fact, a recent survey through Bloglovin showed that 61% of respondents wouldn’t engage with influencer content at all if it didn’t feel genuine.

In late 2016, the term ‘micro-influencer’ started to appear more and more online, and throughout 2017 momentum grew in support of this new breed of influencer collaboration. Unlike the original influencers, who have vast hordes of followers and celebrity status, micro-influencers have a few thousand or tens of thousands of eyes on their activity – but with those lower audience figures come higher engagement rates, and an increased loyalty and trust in what the influencer has to say.

Bar and restaurant chain All Bar One have been hailed as a great success story in the world of micro-influencer marketing, following a three-month ‘brunching’ campaign that saw brunch sales increase by 28% across 50 venues in the UK. The brand worked with ten micro-influencers, with a combined audience of 200,000 people, who generated thousands of engagements and a year-on-year sales growth equal to around 1,800 extra brunches sold per week throughout the campaign.

As a result of successful campaigns like this, micro-influencers’ social channels are currently touted as prime internet real estate for brands looking to grow their audience or to better satisfy their existing target market.

68% of marketers say that finding the right influencer is the most difficult part of the process – finding the balance between an audience big enough to be worthwhile and an audience with a genuine interest in a particular topic isn’t always as straightforward as it seems. 200,000 uninterested viewers won’t be much good to you, but 20,000 likely buyers might be, so finding the balance is as crucial as it is tricky.

Looking to the future of influencer content

In an ideal world, collaborations with micro-influencers would now continue indefinitely as a fantastic way to have natural, authentic content shared with relevant audiences while simultaneously strengthening your brand. But if the first wave of influencers have shown us anything, it’s that too much of a good thing doesn’t last long.

The Advertising Standards Agency in the UK and Federal Trade Commission in the US are wising up to this new form of sponsored advertising, putting pressure on influencers to make it clear if a post has been created as a result of payment or other incentivisation by a brand. Cracking down on misbehaviour is tricky, because it means trying to spot the difference between a genuine opinion and one that’s been paid for – and good influencer marketing is that which appears to be completely authentic.

That said, influencers don’t want to risk having their social media accounts even temporarily disabled as the result of a discrepancy, or being handed a hefty fine for promoting something they’ve been gifted without even receiving a payment. As a result, more and more influencer collaborative content is being marked with hashtags like #Ad and #SponsoredContent – or written with a by-line explaining that the post, video or image has been funded by a brand.

When the whole purpose of moving from influencers to micro-influencers is in the believability and the ‘genuine’ feel of their content, the pressure to clearly label everything as having been backed by a business is damaging. Research by Fractl found that for both big-name influencers and micro-influencers, marking a post as sponsored led to an engagement drop of between 6 and 8%.

So where does influencer marketing go next? For now, micro-influencers are supported by engaged audiences who may be as excited to see their favourite names being picked up by brands as the influencers themselves are to be involved. But as timelines are increasingly filled with sponsored content and trust in influencer marketing depletes, in seems likely that the next big crash isn’t far away as users continue to seek out real reviews and opinions.

The key to continuing success in this field is in genuine relationships. The influencers you work with have to really believe in your brand, and be aligned closely enough with your values and ethos that a sponsorship hashtag won’t matter – relevancy has to be at a campaign’s core to ensure that influencer marketing continues to pay off, but even the most relevant collaborations may soon succumb to a lack of consumer trust.